|

|

|

|

|

|

At the turn of the 20th century the Ku Klux Klan was the law in Indiana and where the heel of Jim Crow's boot lay squarely on the back of black Hoosiers. Possessing the civil rights of a stray dog, there was an Evansville, Indiana shoeshine boy named Charlie Wiggins who would help pave the way for Jackie Robinson to break the race barrier in baseball, Charlie Sifford in golf, Earl Lloyd in basketball, and Willie T. Ribbs to become the first black man to race in the Indianapolis 500.

Charlie Wiggins grew up in a segregated Evansville. The KKK had come to power in Indiana in 1924 would rule state politics and government and D.C. Stephenson, the head and organizing force of the Klan, was an Evansville resident.

Charlie Wiggins, as shoeshine boy, held a fascinatiom with the relatively new automobiles that were coming to town. He would entertain his customers by identifying the make and model of cars by simply hearing the motors as they drove down the street. With a stroke of luck he was shining shoes outside an auto repair shop when the owner offered him a job as an apprentice. Quickly, Charlie rose to chief mechanic and became recognized as the best mechanic in the city. He would often diagnose the car's problem just by listening to the car engine.

Indiana's heritage was rich and played a significant role in the development of the automotive industry. In Indianapolis, there were hundreds of makes and models being manufactured. Charlie realized that greater opportunity lay in Indianapolis and he and his wife, Roberta moved to the state capital.

Charlie and his wife opened a garage on Indianapolis' segregated south side and quickly established himself as the city's top mechanic. He was held in high regard by the city's elite, and particularly by white race car drivers, who were among the top contenders for the Indianapolis 500.

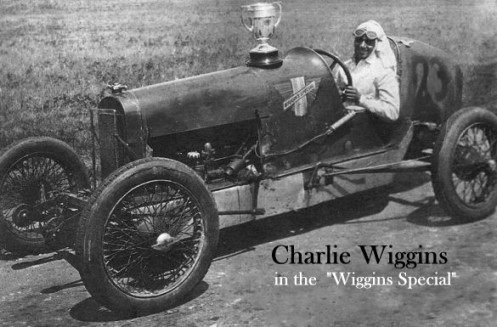

Assembling parts from auto junkyards, Charlie built his first race car, "The Wiggins Special,” which reached speeds on dusty, rutted, dirt tracks as fast as those cars racing on the smooth surface the Indianapolis Speedway.

Every year Charlie would enter "The Wiggins Special" in the Indianapolis 500 and every year the governing body, The American Automobile Association, enforcing unwritten segregation rules, rejected his application.

Charlie and other black drivers formed a racing association and competed among themselves at tracks around the Midwest, attracting large crowds who appreciated exciting racing and Charlie gained a reputation as the top black driver. He became known among fans as "The Negro Speed King".

Donald Davidson, Historian of the Indianapolis Speedway, said, "A race track would get so dusty that the only way you could follow your way around, you couldn't see in front of you or around you, but you could look up and go by the trees and actually drive and when the trees turned, then you knew you were in a turn and then just hope that somebody wasn't in front of you."

Charlie caught the attention of William Rucker, a black, gregarious, cigar-chomping, polite, wealthy, powerbroker among the black and white leaders on Indiana Street, who had great confidence in the black man's ability to advance into the Machine Age. With the backing of several sponsors, Rucker established the Gold & Glory Sweepstakes, an annual 100-mile race of speed and endurance for black drivers on the one-mile dirt track at the Indiana State Fairgrounds.

To gain national attention, Rucker invited Chicago Defender journalist Frank Young to cover the race. On the race's inaugural event Young wrote, "This auto race will be recognized throughout the length and breadth of the land as the single greatest sports event to be staged annually by colored people. Soon, chocolate jockeys will mount their gas-snorting, rubber-shod Speedway monsters, as they race at death defying speeds, The largest purses will be posted here, and the greatest array of driving talent will be in attendance in hopes of winning gold for themselves and glory for their Race."

The Gold & Glory Sweepstakes became a national success, attended by thousands and covered by the national newspapers and newsreel services. Charlie won three of the first six races, performing as both driver and mechanic.

As an outspoken critic of the segregationist practices of the Indianapolis Speedway, Charlie was often a target of the Ku Klux Klan. This harassment became more chilling when in 1930 when two teenage black boys were lynched on the Grant County, Indiana Courthouse lawn. At times the Klan would damage his garage and on several occasions he was attacked physically but he would always fight off his attackers, refusing to succumb to their terror.

When Harry MacQuinn, a white Indy 500 driver and friend of Charlie's, asked to use a "Wiggins Special" in a race at Louisville, "Charlie agreed if he could drive the car during the qualifications to get the engine and car adjusted correctly. When the fans at the Louisville track realized a black man was driving the car, they swarmed the pits and threatened to lynch Charlie. For his safety, the Kentucky Militia arrested him for 'speeding'."

In 1934 Bill "Wild Bill" Cummings was one of the top competitors in the AAA asked Charlie to serve in his pit crew for the Indianapolis 500. The Raceway had strict rules about employment and race, and the only job Charlie could officially hold was that of a janitor. During the days he would sweep and clean as a decoy and then at night would sneak in with the pit crew to help manufacture a racecar for Cummings.

Bill Cummings won the 1934 Indianapolis 500 in what newsreels described as one of the greatest races in Indianapolis 500 history, and for years after, Bill Cummings publicly recognized and thanked Charlie for his skill and expertise in the victory.

In 1936, during the Gold & Glory Sweepstakes, because of poor track conditions Charlie was involved in a 13 car wreck. He escaped death but so severely injured his right leg that they had to amputate. The racing career of The Negro Speed King was over.

With the loss of its biggest draw, 1936 would mark the end of the Gold & Glory Sweepstakes, an institution that had remained financially successful through the height of the Great Depression.

However, Charlie's contribution to auto racing was far from over. He would champion the rights of black mechanics and drivers and continue to fight the segregationist practices of the American Automobile Association. He would train young black mechanics who would contribute greatly to the development of the automobile and racing, and he would be visited at his garage by many important white drivers and mechanics seeking his expertise.

Notre Dame Historian Richard Pierce summed up Charlie by saying, "Charlie Wiggins was a hell of man. We could talk about Charlie Wiggins as a mechanic, his ability as a driver. We could say all those things. And without the pejorative function, without the sexist connotation, we have to say at the end of the day that he was......a man"

Nearly penniless after years of medical costs due to his injuries received in 1936, Charlie Wiggins died in 1979 and was buried in an unmarked grave at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.