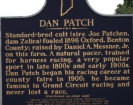

Born in Oxford, Indiana, in 1896 to the mare Zelica, owned by local storekeeper Daniel Messner Jr., Dan Patch (named by combining the first name of his owner with a shortened form of the last name of his sire, Joe Patchen) typified the classic American rags-to-riches tale. At birth his legs were so crooked that he required human assistance to stand up and nurse. Some of Messner's neighbors suggested that the horse be put out of its misery. Most of the townspeople called the colt "Messner's Folly." (Ten years later, these same naysayers bragged about their firsthand knowledge of this wonder horse.)

At first even Dan Patch's owner had doubts: one account states that Messner tried to trade the colt for another in the stable of local livery owner John Wattles. When Wattles refused, Messner paid him to train the colt during the summers of 1899 and 1900. It was in all likelihood the patience and foresight of the septuagenarian Wattles that really produced the "Miracle Horse." Even though Dan Patch showed himself to be game and possessed of some speed, Wattles worked the colt slowly and easily until the horse had achieved full growth at age four. At that age Dan Patch stood as an excellent specimen of horseflesh, standing sixteen hands tall (sixty-four inches) at the withers or base of the neck and weighing in at a hefty 1,165 pounds. He participated in his first harness race on 30 August 1900 in Boswell, Indiana, with reports indicating that he outclassed his competition.

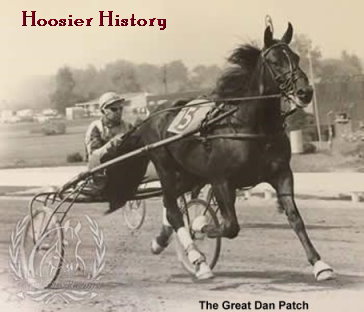

In harness racing, the jockey rides not on the horse's back but instead in a sulky pulled by the horse. Horses used in this form of racing are called Standardbreds and are divided into two groups: pacers and trotters. A pacer (as Dan Patch was) moves its legs

laterally, right front and right hind, then left front and left hind, striking the ground simultaneously. A trotter moves its legs diagonally, right front and left hind, then left front and right hind, again striking the ground simultaneously. At the turn of the century, racing was done in heats. Riders warmed up their horses for a few fast miles and then ran a series of one-mile contests until one horse had won a clear majority, usually three out of five heats.

In a racing career spanning nearly a decade, Dan Patch lost only two heats and never lost a race. The first of those two losses occurred in 1900 in his second start, at Lafayette, Indiana, against what was termed "real competition." In the first heat, Dan Patch started at the back of the field and was dead last at the beginning of the homestretch. Racing accounts said that he passed horses as if they were standing still but lost by a nose to the favorite, Milo S. No one, not even hometown admirers, had dared bet on him. To everyone's surprise, however, Dan Patch captured the next three heats. The other loss in a heat occurred a year later at Brighton Beach. In that instance judges disciplined Dan Patch's driver for "not driving to win," and the crowd nearly lynched the hapless man.

In 1900, as now, harness racing had a class system in which better horses could be "staked" or paid in advance into higher-caliber races that moved from city to city on what is called the Grand Circuit. Encouraged by his horse's early success, Messner wrote Myron McHenry, a New York horse trainer, and asked that he train Dan Patch and race him at the 1901 Grand Circuit meets. Believing that this was just another small-town horse enthusiast with a fast buggy horse, McHenry tried to discourage Messner by telling him of the expense involved and the great odds against any success. But the Oxford storekeeper persevered. Messner shipped Dan Patch to McHenry, and the pacer made his debut on 17 July 1901 in Detroit. He then raced in Cleveland, Columbus, Buffalo, and Brighton Beach. By 22 August at Readville, Massachusetts, Dan Patch's success was such a foregone conclusion that track owners, fearing staggering financial losses, pulled the horse from the betting. During the season Dan Patch became the most talked-about phenomenon on the American sports scene. He finished the year with twelve straight race wins and $13,800 in earnings. Hometown fans hoped that Dan Patch might race at the Grand Circuit meet at Terre Haute before returning to Oxford for the winter, but no one dared to race against him.

Dan Patch returned to Oxford on 2 November 1901. Twelve days later, the town celebrated its first Dan Patch Day, an event that is still observed. The town band played "The Dan Patch Two Step," written by local resident James W. Steele, as it led its honored pacer in a parade around the town square. Accounts of the time remarked about the almost humanlike sense the horse showed in recognizing friends, dancing to the music, understanding what was said to him, and other characteristics of superior intelligence. No doubt admirers gave him a little too much credit, but the legend grew from there. What is amazing to many horsemen is that Dan Patch could be driven around the square like a pet carriage horse only three weeks after his last Grand Circuit race of the season. Even then, after only sixteen starts, the legend of the unbeaten pacer was becoming bigger than Dan Patch himself.

Hometown heroes have always played an important part in the celebration of small-town America, and Oxford looked to a hero that could put it on the map. Humble origins only help to enhance a hero's image, and Dan Patch certainly had them. As many as six hundred newspaper stories appeared telling the story of Dan Patch's background. Newspaper editors sent the horse flowers, politicians campaigned in early 1902 by handing out Dan Patch cigars and balloons to voters, and all the while the subject of this lavish attention-said to be as gentle as a Newfoundland dog-was running around the town of Oxford hitched to a sleigh.

Oxford residents were shocked in March to learn that Messner had sold his famous pacer to M. E. Sturgis of Buffalo, New York, for the unheard-of sum of $20,000. Sturgis, an elderly bachelor sportsman, had McHenry start Dan Patch in three races in 1902, but by July of that year it was no longer possible to find owners willing to submit to the humiliation of being beaten every time or, if a race could be arranged, track owners willing to allow any betting. Sturgis did the only thing possible at the time, pitting his horse against the clock in exhibition trials. The world's record for the one-mile distance for pacing horses in 1902 stood at one minute, fifty-nine and one quarter seconds, a record set by Star Pointer in 1897. By the end of the 1902 season Dan Patch had matched, but not bettered, the record. By December, however, Dan Patch had created another type of world's record for pacing horses.

Newspaper headlines in December announced that Dan Patch had been sold again, this time for $60,000 to Marion Willis Savage, owner of the International Stock Food Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Savage himself was a rags-to-riches success story, and his background complemented that of his newly acquired prize pacer. Born near Akron, Ohio, in 1859, the son of a country doctor, Savage tried his hand and failed several times in farming and agricultural-related businesses before finally starting the International Stock Food Company in 1886. Beginning in Minneapolis with nothing save enthusiasm and energy, he built the world's largest stock food company of its time and became known as an advertising wizard. It is likely the purchase of Dan Patch was initially just another advertising investment for Savage's burgeoning farm supply empire.

Savage had not bought the world's fastest horse or a world champion of any sort. Dan Patch had only tied Star Pointer's record, and even though there were indications that he might go faster, it was Savage who created the "World's Champion Pacing Horse," subsequently making Dan Patch a household name. It is speculated that the Dan Patch name alone made Savage more than $20,000 in his first month of ownership, with the horse never leaving the barn. As a businessman and horseman Savage was obviously the master of the extreme and extravagant. His palatial stable, which he built to house Dan Patch and other champion horses he purchased, became known as the "Taj Mahal." The five-winged structure had steam heat, running water, a blacksmith shop, and a fire engine. It housed 130 horses and 60 employees. The workers had rooms for reading, sleeping, and bathing. The complex boasted a top-of-the-line outdoor mile track and an enclosed, steam heated, half-mile track. Later in Dan Patch's career tourists could visit him on Savage's Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Rochester, and Dubuque Electric Traction Company railroad, which became known as the Dan Patch Line.

The year 1903 saw Dan Patch cement his reputation as the "World's Fastest Pacing Horse," breaking every possible record for that style of racing. During the racing season the horse set new records for the half-mile distance, the one-mile distance (breaking Star Pointer's standard), the two-mile distance, and every other type of record Savage could find for his horse to break. Savage's advertising centered on the pacer, and the names Dan Patch and International Stock Food became synonymous. Advertisements for the company claimed that Dan Patch became the "Undisputed World's Champion" only nine months after commencing his International Stock Food diet. The slogan of "three feeds for one cent" became known nationwide in a country that was still largely rural.

Not all was well, however, in the Dan Patch camp. At the end of the 1903 season, Savage's quest for advertising and image, and McHenry's alcoholic brooding, became incompatible. In a move that shocked the harness-racing community, Savage fired McHenry and replaced him with Harry C. Hersey, an unknown exercise boy from the Savage farm. To Savage his decision made sense, not only because the horse liked Hersey, but also because the businessman trusted the young man to drive and care for the horse and, consequently, International Stock Food's image.

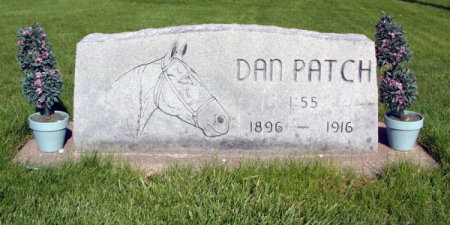

The years between 1904 and 1909 proved extremely productive for Savage and his equine hero. Dan Patch continued to better his times; he paced the mile in a record one minute, fifty-five and one quarter seconds in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1905, and then shaved the quarter second off in an exhibition at the Minnesota State Fair a year later. Though this new record did not become official (the sulky used a dirt shield, which was illegal), fans accepted it, and Savage renamed his farm the International 1:55 Stock Food Farm. Meanwhile, advertising blitzes spread out across the country preceding these and other exhibitions. Advance men plastered posters on fences, walls, and billboards, put pictures and stories in every newspaper and farm journal within three hundred miles of an appearance, and even distributed articles supposedly authored by the great horse himself. Stories of the horse's uncanny intelligence, love of band music, and recognition of photographers appeared weeks and even months prior to any appearance. Traveling in his own railroad car, painted white with his own framed portrait on each side of the car, Dan Patch encountered throngs of admirers at every stop.

Savage never required an exhibition fee for Dan Patch's appearances at county and state fairs and Grand Circuit meets; he agreed instead to receive either a percentage of total gate receipts or the receipts in excess of those received on the same day of the previous season. Occasionally fair officials were so staggered by the number of fans who flocked to see Dan Patch that they were reluctant to pay Savage his share. Figures early in the horse's racing career indicate that crowds of 40,000 to 50,000 and more were common. In Muncie, an appearance that came almost at the end of the horse's career, 20,000 people jammed the fairgrounds to watch an exhibition race between Dan Patch and his stablemate Minor Heir. At that time, the total population of Muncie numbered fewer than 23,000 people. No emotion was ever spared in the creation of the Dan Patch legend. Even when ill and not racing, the horse benefited his owner. In 1904 Dan Patch became seriously ill while in Topeka, Kansas. The Chicago Tribune carried

the story and said there was little hope, while the New York Times' report seemed guardedly optimistic. The best veterinarians in the Midwest were summoned. Reports had Savage chartering a special train and arriving late that night with International Stock Food patent remedies. Savage and his International Stock Food's Colic Cure were credited for the horse's miraculous recovery.

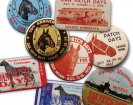

Dan Patch's fame grew with each year, and so did Savage's advertising gimmicks. The champion endorsed sleds, coaster wagons, the Dan Patch Automobile (which cost $525), tobacco, gasoline washing machines, and just about any product associated with International Stock Foods. In all thirty products were licensed with Dan Patch's name. Savage also designed and gave away many other advertising specialties such as watercolor portraits, thermometers (an original Dan Patch thermometer for sale at an Indiana antique store in 1998 cost $3,000), and assorted other logo-related freebies. Some estimates say that Savage made about $13 million on the Dan Patch name alone; figures are sketchy, however, and the total profit could be considerably higher. Even more funds poured in from the growth of International Stock Food. The company's business increased from $1 million to $5 million in the first year that Savage owned Dan Patch.

Savage's promotional skills earned him the distinction "the second [P. T.] Barnum." He purchased two dog-and-pony shows from Gentry Brothers of Bloomington, Indiana, and put these shows on the road promoting International Stock Food and Dan Patch. Among other features of these rather ornate circus operations was a movie of Dan Patch pacing his unofficial world-record mile at the Minnesota State Fair. (Flip-card versions of the film were also sold for ten cents. All forty-eight cards in the matchbook-size package had International Stock Food advertising on the reverse.) The shows also featured a canvas wagon pulled by eight dappled gray Percherons, each with a brass plate on its harness that read, "Pals of Dan Patch. International Stock Food Company, Minneapolis, Minnesota." The horses probably never saw Dan Patch, however, because they wintered in Bloomington every year.

In 1909 lameness forced Dan Patch to retire. He raced in an exhibition at Los Angeles and drew up visibly limping at the end of the mile. He was retired to stud and spent time accompanying his stablemates Minor Heir and George Gano on their exhibition tours. Dan Patch's success as a sire was limited, and he failed to pass along his greatness to any of his offspring. Just as he had marketed Dan Patch, Savage marketed the famous pacer's offspring as though they were the end-all advertising kit for growing businesses everywhere. Even if any of these colts and fillies had shown promise, it is doubtful they could have had the draw their charismatic sire had maintained for so many years.

Savage and Dan Patch benefited during the zenith of harness racing's popularity. America's sporting tastes, however, changed rapidly. Horse transportation and horses as sport were swept aside like outgrown toys in the face of industrialization. Dan Patch's name endorsed the very product that would seal the fate of the horse as a prime mover: the automobile. Dan Patch and his owner did not live to see the new age of mechanization fully blossom, though. The pacer and his owner both fell ill on 4 July

1916. Dan Patch died of an enlarged heart on 11 July. Savage was in a Minneapolis hospital for minor surgery when informed of his horse's death. After the initial shock, he made arrangements to have Dan Patch's body stuffed and mounted for display. Before his order could be fulfilled, however, Savage died, only thirty-two hours after his champion pacer. Savage's wife, Marietta, had the horse's body recalled from the taxidermy shop and secretly buried. During the next two years the racing and breeding stock of the International Stock Food Farm was sold, the farm ceased operations, and Savage's other business interests began a long decline. Today, where the "Taj Mahal" once stood, there is nothing but an empty field.

International Stock Food may be gone, but the name of its icon, Dan Patch, lives on overt a hundred years later, stubbornly refusing to die. The Hoosier Park horse-racing facility in Anderson is located on Dan Patch Circle. The park's annual feature race for pacers is called the Dan Patch Invitational. Writers and horsemen have debated for almost the whole century as to who made whom. Did Dan Patch make Savage, or did the showman advertiser create the "World's Greatest Pacer"? That debate will probably continue. What is known by most horsemen, though, is that Dan Patch was a century ahead of his time. His official pacing record for the one-mile distance stood for thirty-three years before being broken by Billy Direct in 1938. It was another thirty years before the record was substantially lowered, and only in the late 1980s and 1990s have pacers raced at speeds that Dan Patch paced every day.