|

|

|

|

|

|

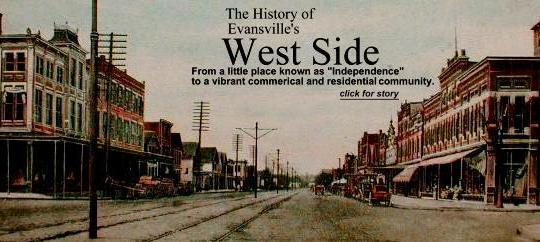

The West Side of Evansville, Indiana has, in local terms, considerable historical and cultural significance. For many years it was physically cut off from the main part of the city by Pigeon Creek and the wide swath of factories that once made the creek an important industrial corridor. Further isolated, culturally, by a heavy settlement of German immigrants in the late 1880s, the West Side developed in its own way and at its own pace. By the turn of the century it had achieved a strong sense of community and self-sufficiency.

The West Franklin Street area became a retail and service center second only to downtown. The 100-foot-wide street itself became something of a civic plaza. Neighbors, sharing ties of family and ethnic background, gathered there to socialize as well as to conduct business. When farmers from the western townships-who shared many of the same family and ethnic bonds -came into town to do their weekly “trading,” “town” to them most often meant West Franklin Street.

The West Franklin district extends across the center of the western half of a 480-acre (more or less) tract of land, bisected by Pigeon Creek that was platted in 1837 as the “City of Lamasco”. The proprietors were John and William Law, James B. McCall ( or Macall) and Lucius H. Scott, and the novel name of their town was constructed from the first letters of their surnames. While the portion east of the creek developed into a town and was incorporated in 1847 as Lamasco City, the part to the west remained largely unsettled. By the 1860s it had acquired the name “Independence,” possibly because it had retained its independent status when Lamasco City merged in 1857 with Evansville.

In the years following the Civil War, Independence began to experience an influx of settlers, most of whom were of native German stock. The increasing population of the area and its development potential made it an attractive target for Evansville expansion, and in spring, 1870, the Evansville Common Council announced its intention to annex the area. To counter the annexation action, some residents proposed incorporation as a separate town with the name “Madduxport” after Alexander Maddux, a justice of the peace. However these plans proved useless. By early summer, Independence was made a part of the Evansville Municipality. “Independence” as a named lingered in usage for a time, but eventually it gave way to the geographic designation “West Side”.

While annexation did not produce a surge of development for the area during the 1870s, it did provide benefits such as metropolitan fire protection and the construction in 1876 of the three-story brick Centennial School. An event of the 1870s that augmented the established saw mill and coal mining industry was the relocation in 1875 of the downtown-based Evansville Cotton Mill into a new, mammoth factory on St. Joseph Avenue near the Ohio River. The move infused new capital into the area, and workers living in the adjunct tenement block further increased the population. By the end of the decade, West Franklin Street was showing signs of becoming a commercial strip, although there were still on a handful of businesses, mostly quartered in frame buildings and strung out along the roadway. Housing stock was equally unpretentious , except for the Wabash Avenue “mansion” of sawmill owner Charles Schulte that was built in 1878.

The 1880s and 1890s in Evansville were a period of great growth, which spilled over into the relatively vacant lands of its west side. The river and creek banks lined with factories and milling operations turning out boxes, brooms, edge tools, flour, and planed and dimensioned lumber. Residential blocks became filled in with new housing. Streetcar service was extended into the area 1882 via Franklin Street, and, no doubt, encouraged the area’s growth and the street’s development.

The same year, the twin-spired St. Boniface Church went up on Wabash Avenue. In addition to providing the West Side with a stately landmark, the church served as a centerpiece for a boulevard of large homes which were erected for some of the community’s business and civic leaders. In 1884, West Franklin Street received its first impressive building – the Lava Block. The construction of similar structures followed in the 1890s.

The growth and urbanization of the West Side continued on into the new century. The rough slopes of Coal Mine and Babytown Hills on the western edge of the low-land community were transformed into West Side residential districts, and the top of Coal Mine Hill was crowned in 1918 by the classically designed Francis Joseph Reitz High School. Industry became more diversified, notably by the establishment of Helfrich Pottery enterprises and by the Globe-Bosse-World Furniture Company, which was touted at the time as the “world’s largest” company of its kind. West Franklin Street acquired a respectable “Main Street” appearance as, new, well-designed commercial and institutional structures filled in vacant lots or replaced modest buildings of earlier times. In its role as community socializer, it helped to foster the emergence of a widespread and unequalled sense of civic pride that resulted in the formations of organizations specifically for the betterment of the area. Such organizations still exist, and the vigorous pursuits of, for example, the West Side Improvement Association and the West Side Nut Club, are evidence that the attitude the “West Side Is The Best Side” is still a potent force.

Like other traditional shopping hubs, West Franklin Street faces an increased competition from commercial development on the city’s outskirts, Yet the district has a charm and vitality not found in modern suburban commercial centers. Its spruced up buildings and attractive landscaping, and its small town atmosphere within the larger city – the feeling of a place where neighbors still greet one another and feel comfortably “at home” make historic West Franklin Street as congenial a destination for generation of West Siders as it was for their forbears.

Text Courtesy of the City of Evansville

Photographs Courtesy of Willard Library